By:- Vigorosityhub

4 Surprising Truths About the Price-to-Book Ratio (Even Buffett Called it ‘Meaningless’)

Introduction: The Metric You Think You Know

For many investors, the Price-to-Book (P/B) ratio is one of the first valuation tools they learn. It’s a classic metric, long associated with the time-tested principles of value investing. But while it may be familiar, its true meaning and application are often deeply misunderstood. Relying on conventional wisdom when using the P/B ratio can be more than just unhelpful—it can be actively misleading.

The simple idea of buying stocks for less than the value of their assets seems straightforward, but the reality is far more complex. There are surprising truths and paradoxes hidden within this ratio that can fundamentally change how you view a company’s value. Here are the four most impactful and counterintuitive takeaways about the Price-to-Book ratio.

Takeaway 1: The World’s Most Famous Value Investor Called It “Meaningless”

While the P/B ratio was a cornerstone for early value investors like Benjamin Graham, his most famous disciple, Warren Buffett, has expressed a starkly contrary view. In his 2000 annual report, Buffett delivered a blunt assessment of book value’s relevance.

“In all cases, what is clear is that book value is meaningless as an indicator of value”.

Why would the oracle of value investing dismiss a foundational value metric? The reason lies in the economy’s shift from tangible to intangible assets. In the modern era, a company’s most valuable assets are often intangible and are not reflected on the balance sheet. Assets such as brand awareness, intellectual capital, copyrights, and internally generated goodwill can be far more valuable than the physical assets listed in a company’s balance sheet. For Buffett, book value has become a poor and often irrelevant indicator of a company’s true intrinsic value.

Takeaway 2: …And Yet, Low P/B Stocks Still Mysteriously Outperform

This is the main price-to-book ratio dilemma. Despite its obvious drawbacks and scathing critique from analysts such as Buffett, a large amount of scholarly research has consistently shown an intriguing pattern: equities with low P/B ratios typically perform better over the long run than those with high P/B ratios.

This phenomenon is so persistent that influential researchers Eugene Fama and Kenneth French incorporated a price-book term into their influential three-factor model, a foundational framework for explaining stock returns. This is the core puzzle of the P/B ratio: how can a metric that Buffett rightly calls ‘meaningless’ for valuing an individual modern business still have such consistent predictive power across the entire market? It suggests that while book value may fail to determine a specific company’s intrinsic worth, it still reveals something powerful about market behaviour and future returns.

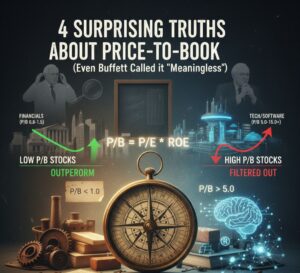

Takeaway 3: A “Good” P/B Ratio Is All About the Industry

The P/B ratio means little on its own but can speak volumes when compared to industry averages. Because different industries rely on different types of assets, what constitutes a “high” or “low” P/B ratio can vary dramatically. Comparing a bank’s P/B to a software company’s is a fundamentally misleading exercise.

Consider the typical historical averages for an asset-heavy industry versus an asset-light one:

| Industry | Typical Historical P/B Average |

| Financials (Banks, Insurance) | 0.8 – 1.5 |

| Technology / Software | 5.0 – 15.0+ |

P/B is a key valuation tool for banks and insurance firms, whose assets (such as loans and investments) are continuously valued at market prices. The P/B ratio is most impacted by Return on Equity (ROE) for these companies, and a value less than 1.5 is typical. On the other hand, a technology company’s balance sheet shows few physical assets, but its intellectual property has enormous earnings potential. Here, an extremely high P/B ratio is a reflection of the market’s expectations for future growth from intangible assets rather than necessarily an indication of overvaluation. “High or low relative to what?” is the first rule of using the P/B ratio, rather than “Is it high or low?”

Takeaway 4: The Hidden Trap: Why Low P/B Can Filter Out High-Quality Companies

What if the secret to finding the market’s highest-quality companies was to look for a high Price-to-Book ratio? For many investors, this sounds like heresy—but the math proves it can be true. A common mistake is to screen for stocks with both a low Price-to-Earnings (P/E) ratio and a low Price-to-Book (P/B) ratio, believing this is the key to finding “value.” In reality, this strategy may systematically filter out the highest-quality companies.

The reason lies in a simple mathematical relationship: PB / PE = ROE (Return on Equity).

Let’s break down the logic. A high-quality company is one that generates a high return on its equity (ROE)—for example, a quality business might have an ROE of 20%. If that company trades at a reasonable P/E ratio of 20, the math is unavoidable. SinceP/B = P/E * ROE, its Price-to-Book ratio must be 4.0 (20 x 0.20). A high P/B isn’t a fluke; it’s the mathematical signature of a high-quality company trading at a fair price. By strictly searching for a low P/B, an investor would have automatically excluded this highly profitable and resilient business.

This mathematical reality perfectly aligns with Buffett’s evolution away from Graham’s deep value. He shifted his focus from cheap assets (low P/B) to wonderful businesses (high ROE), understanding that a high P/B is often the natural consequence of the quality he seeks.

Conclusion: A Compass, Not a Map

In the end, the P/B ratio is a masterpiece in context: a metric that academic models show works but that some of the world’s best investors reject; a figure that is meaningless without industry comparison, and a possible indicator of quality just when it appears high. The P/B ratio functions more like a compass that, when combined with other tools, can help guide you in the right direction than a map that provides you with an exact location.

Now that you see the hidden complexities, how might you change your own definition of a “value” stock?

Concise Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only and is not financial or investment advice. It discusses the Price-to-Book ratio and market concepts, but readers must understand that investing involves risk, and past results don’t guarantee future performance. Always conduct your own due diligence or consult a qualified professional before making investment decisions.

Leave a Reply